The correct takeaway motion is really--in my opinion--a near total function of the rearward rotation of the right latissimus dorsi muscle, with zero arm lift initially and zero movements of the forearms, wrists, and elbows. By that I mean, once you've established a great setup (P1 position - see GASP), the simple, centered pivot movement of the ribcage (upper torso rotation or the "lat dowel" concept) will relocate the unchanged address configuration of the arms and club into a position (P2), where the club is both parallel to the target line and parallel to the ground, without any movements of the arms, wrists, hands, or elbows, and without any lifting from the shoulders before reaching P2. In all golf shots, including the putt, the right latissimus dorsi muscle can be thought of as the motion initiator from a static address position at P1; the right lat moves the club—not the arms.

The feel for me is that the club and arms move as an unchanged unit more around rather than up (up to P2), due to the immediate rearward and targetward rotation of the right lat muscle (the right shoulder moves back as the left shoulder moves across to a point just under the chin). The word “immediate” means that that the right rib cage turns “inside the feet,” with no sway of the right lat muscle towards the right leg. Because I use a relaxed neutral-to-strong left hand grip (heel of the left palm points at my right hip), the left hand remains initially cupped as it was in its address position, meaning that the angle formed by my left arm and club shaft (from my perspective looking down) at address does not straighten at all; if the angle did straighten, I would be flattening my left wrist and/or rolling my left forearm open--both unnecessary moves that require timed compensations to overcome on the downswing. The grip, arms, wrists, elbows, and shoulders are very relaxed and pliable, moving only in response to the initiating move of the right lat muscle rotating immediately back and towards the target.

Another important feel is that the right latissimus dorsi muscle’s rotation freely “slings” or tosses the arms and club through the P2 postion and up into the P4 position (top of backswing). Therefore, the P2 position can be thought of as a “pass through” position—not a point of definitive rest, and perhaps the “P” designation of golf positions would be better suited to mean “pass through” in lieu of “position,” as only P1 and P9 represent static moments in time.

During this move of the right lat muscle to the rear and towards the target, pay attention to the corresponding motion of the left shoulder. The left shoulder should not dip downward towards the left foot in the takeaway, which is advice that is often given to golfers (i.e., point the left shoulder at the ball going back). Some instructors even demonstrate this faulty move by placing a club across the shoulders and pointing the shaft directly at the ball going back. Often this motion is overdone, kinking the upper spine, and the golfer’s upper spine will tilt towards the target (instead of away from the target as it should); more pressure or “weight” will build into the left leg instead of the right (i.e., reverse weight shift or pivot). In reality, the right amount of “dip” is applied simply by the golfer’s primary spine angle or forward posture that’s set at address; it’s not necessary or beneficial to add more dip of the left shoulder going back in order to “steepen” the shoulders. The correct feel is that the left shoulder rotates across and over to the chin, due to the motion of the right lat rotating back. If you’re a “left shoulder dipper” then this motion will feel very flat—as I said in the beginning “more around and then up.” Remember this for short games shots too, such as chips, pitches, and greenside bunker blasts.

Looking down at P2 from the golfer's perspective, he will see the club's grip as roughly bisecting or lying across the instep of his right foot, with the left arm angled backward; this is an illusion of perspective, because the club shaft is really situated closer to the golfer's toeline from an observer's down-the-line view (i.e. the golfer's eyes are out towards the toes due to his inclined posture).

From this point onward, the right lat continues rotating backwards, towards the target, and now the arms and club's momentum from torso rotation move them very slightly and vertically up, where the hands will be over the right shoulder. The club should feel very light going back and up—almost weightless—as it’s being “flung” to the top, where it feels somewhat like it’s floating there momentarily. The right elbow bends and the wrists cock, creating a top of backswing position (P4), where the club shaft is now roughly parallel again to the target line and the ground. The key is that the arms and club are now in deeper positions than at P2, and that depth was created exclusively by torso rotation--not by pushing or pulling the arms horizontally across and around the body. The two lines formed by the shaft at P2, P4, and P6 (prior to impact) can be imagined as forming the top and bottom of a tilted parallelogram, when viewing a golfer from a down-the-line perspective. Without the depth created at the top (P4) as described, there is little room or hope for swinging the club back down from the inside.

On the downswing, while reversing the vertical drop of the arms and club coupled with torso rotation (moving the “lat dowel”), the shaft will again pass roughly back through the bottom of the parallelogram at P6, just before impact. Both hands make a fast, fairly vertical semicircle from above the right shoulder down to the right thigh, as the shoulders rotate back to parallel with the target line; outside-in swings occur when the hands move out (instead of down) from this deeper vertical position, before or as the shoulders turn. And again, the  club should feel light. This motion of the arms and club to get to P6 should feel very vertical; the arms and club return from their deeper position, again, due to the revers

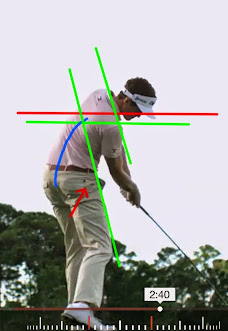

club should feel light. This motion of the arms and club to get to P6 should feel very vertical; the arms and club return from their deeper position, again, due to the revers al of body rotation—not by moving the arms and club out at the ball, which would make the club feel heavier. There is no outward deployment of the club head towards the ball until the club has passed below P6, when physical forces—not the golfer's intention—will naturally deploy the club head outward from the fulcrum of the wrists. Observe the attached graphics of Rory McIlroy swinging a driver. At the top (P6), notice how far around his right lat muscle has rotated around behind him, towards the target. The red lines depict the top and bottom of the parallelogram, while the green lines represent the difference in depth (or tilt) between P2, P4, and P6 (just before impact). Notice how the club and arms drop more vertically down from the top rather than out towards the ball—the amount of depth is about 1.5 feet between P2 and P4. In reality, this is just another way to think of the classic swing plane. The torso is rotating forcefully, but the arms and club are dropping rather than swinging out, which is a golf swing illusion that causes many problems.

al of body rotation—not by moving the arms and club out at the ball, which would make the club feel heavier. There is no outward deployment of the club head towards the ball until the club has passed below P6, when physical forces—not the golfer's intention—will naturally deploy the club head outward from the fulcrum of the wrists. Observe the attached graphics of Rory McIlroy swinging a driver. At the top (P6), notice how far around his right lat muscle has rotated around behind him, towards the target. The red lines depict the top and bottom of the parallelogram, while the green lines represent the difference in depth (or tilt) between P2, P4, and P6 (just before impact). Notice how the club and arms drop more vertically down from the top rather than out towards the ball—the amount of depth is about 1.5 feet between P2 and P4. In reality, this is just another way to think of the classic swing plane. The torso is rotating forcefully, but the arms and club are dropping rather than swinging out, which is a golf swing illusion that causes many problems.

When Things Go Wrong

Performed as described, this is a very effective method of swinging the golf club and producing excellent, consistent contact and ball flights. But there are a few key places where things can go wrong, and you'll notice when contact consistently suffers and you get unpredictable ball flights:

- Monitor your grip positions—especially the left hand. Remember, the heel of the left palm should point at the right hip at address (palm on top), which is essentially a strong grip position. This helps prevent flipping the wrists at impact, which is often an unconscious compensation for an open club face position. The stronger grip allows you to lag the club and square the face, without any compensations. Keep your left hand grip relaxed and correctly pressured by the fingers. The last three finger tips of the left hand should be pulling the grip upward into the heel of the left palm. Keep the right hand grip fairly neutral (examine Rory McIlroy’s grip).

- At address (P1), look down at the angle formed by your left arm (with its strong left hand grip) and the club shaft. The angle is rougly 120 degrees or so. You must maintain that left arm-club shaft angle during your torso rotation to P2, before lifting to the top. This means the club shaft and hands will move well inside

- Be wary of the unconscious tendency to activate any of the arm, wrist, or hand muscles to move the club into the described "tilted parallelogram" positions. For example, noticing where the club and arms move as a result of the right lat moving first, one may unconsciously change focus and begin placing the arms and club into those positions, using the arm muscles (i.e., club shaft bisecting the right instep at P2). These positions are the ends and not the means. The cure is to again focus solely on moving the right lat (the "lat dowel") back and towards the target as the only initiating move, the momentum of which actually “slings” the club into position. The arms, elbows, wrists, grip, and shoulders should remain relaxed and pliable; they are followers—not initiators or assistors.

- Remember that the feel is more around with the arms and club (due to torso rotation) rather than up (shoulder tilt or arm lift). You may also fall into the trap of the right lat moving back but also forcefully up, which will send the left shoulder sharply down toward the left foot and elevate the arms and club more than necessary. This can cause a reverse pivot and place your upper swing center too far forward. Your maintained posture supplies all the "up" that's required. The correct feel is that the left shoulder moves across from your perspective—not down! When the pivot is conducted correctly, the upper swing center (the base of the neck) stays back where it should be.

However, his shoulder rotation can be considered to be relatively horizontal, and there is no dipping of the left shoulder down towards the ground. From a biomechanical perspective, his shoulders are rotating nearly perpendicularly around the axis of his mid-upper thoracic spine, and this natural upper torso rotary movement should occur naturally/automatically without any need for conscious thought. ~ Backswing

One last thought - avoid dipping your left shoulder as you initiate the backswing. You want to turn away from the ball with your left shoulder, not drop it! To avoid dipping, pull around with the right shoulder. The left will follow without excessive dipping. ~ Maintain a Proper Takeaway to Succeed

First, when turning your right shoulder back you must keep you right arm away from the direction of your right shoulder turn. What you should feel is the right arm should try to stay extended away from your body only allowing the wrist to set back behind your head. Second, simultaneously turn your right shoulder back behind your right ear on as level of a turn to the ground as possible. This way the shoulders should turn flat to what ever spin[e] angle you have at address (no dipping). By the way, your left shoulder is not pulled under your chin, it comes up to under your chin (level shoulders to spin[e] angle). ~ Make a Better Shoulder Turn

I found over the years having my students push straight back using their front shoulder, would wind their shoulders around their spine, BUT I have found some golfers push their front shoulder DOWN instead of around their spine. This can lead to problems. ~ The Takeaway Using the Front Shoulder

The shoulder turn moves the club inward, NOT back and up. So if the player just turned their shoulders, without any hand or arm movement, then the club would be inside but not back and up. These two movements MUST work together to achieve the proper sequence. The trailing forearm moves the club on Plane by "tracing" the Plane. The bending, and folding of the trailing elbow also raises and lowers the club and cocks and uncocks the target side wrist. Never raise the arms and club by lifting from the shoulders sockets! ~ The Golfing Machine

In the completed grip, the main pressure points are the last three fingers, with the forefinger and the palm pad adding assisting pressure. The three fingers pressed up, the pad presses down, and the shaft is locked in between. ~ What Would Hogan Do? - Grip

Many people lift the club too soon with their arms, while even more suck their arms behind their bodies and either come over the top, or lift the arms late and then drop them back behind the body and get stuck. ~ Throw it Over Your Right Shoulder

When you start your takeaway, the first thing you should think of is a one-piece move with your shoulders, arms and hands and club) moving together. There is no independent action with your hands wrists or even your elbows. For the first 2 feet or so, nothing should move independent of your upper body moving together. ~ Using Your Arms in the Takeaway

Once mastered this activation of the Latissimus will pull the right shoulder back and push the left shoulder forward creating the perfect initial takeaway position everytime. This will also set up the body allowing the right sequencing of the kinetic chain from shoulders to tru[n]k to hip motion for an efficient and strong backswing. ~ The Perfect Golfswing Takeaway